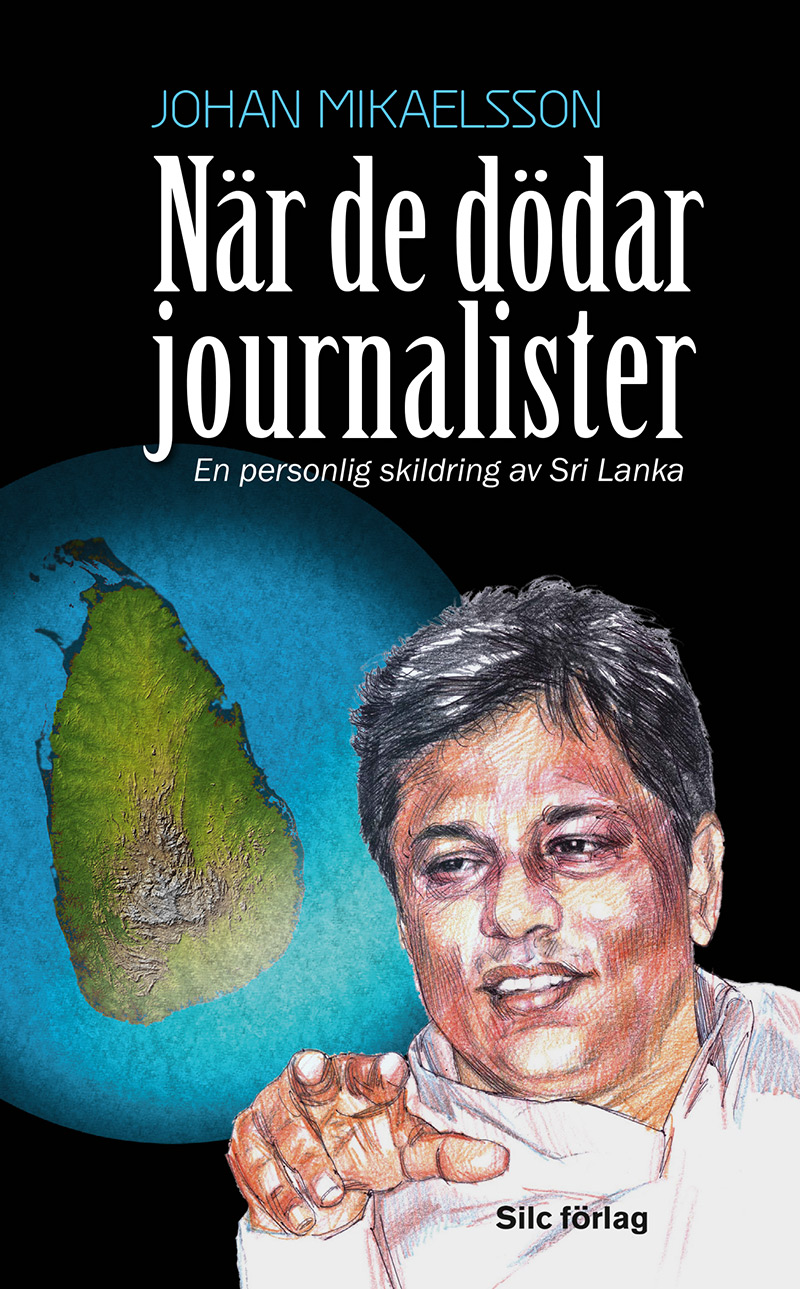

About When They Kill Journalists

”When They Kill Journalists is a creative non-fiction book about the conflict in Sri Lanka. It’s the exciting, personal story of Swedish freelance journalist Johan Mikaelsson and his dedicated effort to get close to a war that is supposed to be creating peace. For three decades a civil war between the Sri Lankan government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), the guerrilla group that fought for an independent state in the north and east, ravaged the country. The reverberations of the war’s bloody conclusion in May 2009 continue to impact on both the island’s people and the outside world.

The book covers the period from 1997 up to the present. It focuses on the conditions of civilians living in war-affected areas of the country, human rights violations and the difficult conditions faced by journalists in Sri Lanka. The book offers insights both sobering and penetrating into a country that for many years was ranked by ‘Reporters Without Borders’ as one of the worst in the world for press freedom. In the book, journalists working on the island tell of truth-seeking, media practices—and the murder of colleagues.

Initiated in the early 2000s, the Norwegian-led peace process in Sri Lanka eventually collapsed, costing tens of thousands of lives. Tamils in the guerrilla-controlled regions longed for peace: instead, from autumn 2006 onwards they were engulfed in another phase of war, finding themselves squeezed between retreating Tamil guerrillas and advancing government forces.

The book provides an understanding of contemporary Sri Lanka—a country all too often perceived as something of a mystery. It is both a guide to Sri Lankan history and the current situation, and offers clues to the country’s future trajectory.

The book is divided into two parts; “Not Only Somebody Else’s Civil War” and “The Past Is Alive”. The first part describes Mikaelsson’s trip to Sri Lanka in 2012, and continues with a look back at the years 1997-2012. The second part begins with another trip to the island in 2012 and continues with events in Geneva at two sessions of the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), where lobbyists argued for justice and a political settlement capable of delivering a just peace, demilitarization and reconciliation. In March 2014 the Council voted for a resolution that mandates independent investigators to look into alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The book includes eyewitness accounts of historical events such as Tiger leader Prabhakaran’s only press conference (2002), and the Commonwealth summit in Colombo in November 2013, when war crimes suspect President Mahinda Rajapaksa was pushed hard by international media, not least a team from Britain’s Channel 4 and Callum Macrae. Macrae’s acclaimed documentary films, with the main title Killing Fields of Sri Lanka, offer an insight into government forces’ intentional bombing of civilians, other abuses and the execution of captured guerrilla cadre.

The second part of the book includes interviews with mediators, ceasefire monitors, journalists, human rights lawyers and representatives for the Sri Lankan government.

The English version of the book will include new chapters on developments after the power shift in January 2015, based on five new reportage trips to the island and several visits at the Human Rights Council in Geneva. In March 2019, Sri Lanka must report to the council on the reconciliation process and show some progress in the investigations into war crimes.

Overall, past and present are bound together in this captivating story about Sri Lanka”.

My First Meeting with ‘Taraki’, Colombo April 1999

I have an appointment with Taraki at an outdoor cafe in central Colombo. The heavyweight reporter is sitting with three colleagues at a table. Each of them is holding the glass of beer that has just been brought to them, and they’ve all had enough time to sink the first draught. Taraki wipes the foam from his upper lip. In 30-degree afternoon heat a beer is a comfortable, and for many natural thirst-quencher. “Mr. Taraki?” “Yes, I suppose that must be me”, he says in a murmur, looking at his friends and laughing.

His real name is Dharmeratnam Sivaram, and his friends call him ‘Siva’. The pseudonym Taraki has been borrowed from a Pakistani army commander. He writes for the Sunday Times, Daily Mirror and Wednesday newspaper Midweek Express. In sharp, analytical articles he puts his finger on the pulse of current issues relating to the conflict. He also writes in Tamil newspapers and is said to be behind TamilNet, a news site directed at Tamils and those around the world interested in Sri Lanka. It is one of the few news sources in English that covers events in the war-affected parts of the Island.

I sit down on a chair opposite the four men. The shade provided by a sun umbrella feels good. After a few opening pleasantries I order coffee and ginger beer from a waiter in white shirt, black jacket, bow tie and black trousers. I turn on the tape recorder, only to discover that I am the one being questioned.

“So what do you think about TamilNet?” Sivaram begins. “The site would appear to enjoy a high level of credibility,” I answer. ”So there’s substance in its reporting?” “I think so. But it’s hard to know because reporters aren’t allowed to visit the war zone. You’re involved in TamilNet aren’t you?” “Says who?” “Someone told me”, I answer evasively, as I don’t want to reveal my source. “Who? The government?” “No, not the government, another journalist.”

Since the government accuses TamilNet of having contacts with the LTTE and promoting their views, Sivaram is reluctant to be linked publicly with the site. TamilNet has reporters in the northern and eastern parts of the island, including inside the guerrilla-held areas. Sivaram’s articles differ from those of other reporters. He gets closer to the core of the conflict. From his articles I have sensed that he has a deeper understanding of the suffering the conflict causes than most others writing in the English language media.

“What have they said about my writing?” “I don’t think anyone has said anything in particular”, I respond. “Except perhaps that you have a different view from that of other journalists.” “How so?” “Well, you are perhaps more Tamil-friendly.” “You use fine words”, he says, laughing out loud. “In English it is known as a euphemism. Extremists can also be called ‘Tamil-friendly’”, he says, and laughs again.

At Guerilla Leader Prabhakaran’s Press Conference, Kilinochchi, April 2002

Fifteen minutes later, more SUVs arrive at high speed. They brake, we hear car doors being opened, and the gates are opened. In comes the Tiger leader. He is surrounded by plainclothes bodyguards along with several of his colleagues from the guerrilla’s top leadership. The soldiers shielding him from every conceivable angle of fire obscure Prabhakaran himself. Photographer Dominic Sansoni is upset.

“You must understand that it’s also good for you if we can take a real picture of Prabhakaran”, he says aloud to some Tigers officials. “Come on now, we’re just asking for one picture”, he appeals in frustration to Prabhakaran himself, who is standing about six feet away, on the other side of a wall of bodyguards.

The appeal falls on deaf ears. The Tiger’s stubborn temperament is firmly to the fore here. Those responsible for bodyguard protection of the leader do their job, with no deviations from their original plan. There is to be no organized photo opportunity with Prabhakaran looking into the camera. Sansoni kicks the ground in frustration, sighing loudly. I photograph the moment when Prabhakaran passes by, partly obscured by a branch that hangs down from the tree closest to the building. I’ll have to wait for the results until we can develop the film rolls. The expression ‘Kodak moment’, which Olle and I use in Sri Lanka, remains as relevant as ever.

I return to building in which there 200-300 journalists are gathered by now. Most are local Sinhalese and Tamil reporters. A large group of Indian journalists have also travelled here. Only about 20 or so pale Westerners, from colder northern climates, stand out in the assembled crowd. I make my way through the crowd and reach Olle just as ideology chief Anton Balasingham and his Australian-born wife Adele take their places on the podium. Vinayagamoorthi Muralitharan, leader of the Tiger forces in the East known as ‘Colonel Karuna’ and political wing leader S.P. Thamilchelvan are also sitting on the podium. This is the guerrilla’s united front: only Pottu Amman is missing.

Prabhakaran has light grey trousers: below the collarless, short-sleeved shirt in the same fabric he seems to be wearing a bulletproof vest. The moustache is gone. The clean-shaven face and clothing, later described as a ‘safari outfit’, is interpreted as another sign of a ceasefire, relaxation. Prabhakaran has acquired the habit of shaving off his moustache during periods of peace negotiations. Most of his colleagues, however, do not appear to be following their leader’s example. Behind the five cadres on the podium stand bodyguards with dark aviator glasses, short-sleeved white shirts, dark trousers and a pistol in their waistbands.

Anton Balasingham begins to speak. “I want to welcome you to this press conference and to thank you for having taken yourselves all the way here to Kilinochchi, despite all the difficulties. You have now seen for yourselves the devastation the war has caused in our part of the country. Mr Velupillai Prabhakaran is both prime minister and president of Tamil Eelam, and I will translate all the answers to your questions”, says Anton Balasingham.

The press conference has started, and I feel as if we’re taking part in a decisive event in the history of this conflict. At first it seems as if Prabhakaran is a little uncomfortable, but soon it transpires that he is interested in and focused on the issues at hand — with the help of his closest advisors sitting to his right, answering all the questions. Questions revolve around the upcoming peace talks in Thailand.

Scene from a Press Conference with President Rajapaksa

at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting

in Colombo, November 2013

Ranga Jayasuriya from Ceylon Today teeters on the borderline when he asks the President what he thinks of British Prime Minister David Camerons statement following his visit to former war affected regions. The president smiles and tilts his head to the side when he sees the young journalist with curly hair whose voice trembles a little when he asks his question, clearly aware that he is on dangerous ground.

“I would like to put a question to President Mahinda Rajapaksa”, he begins, and the President bends forward towards his microphone. “There are others here as well”, says the President. “You don’t need to put questions only to President Rajapaksa”, Richard Uku adds. Ranga Jayasuriya doesn’t allow himself to be deflected.

“My question relates to what Prime Minister David Cameron said, namely that if the Sri Lankan government fails to complete its own investigation of alleged war crimes by March next year, he will push for an international investigation”, he begins. “That is his opinion. This is a democratic country. We are all equal, and he and others can say what they want. It is up to them”, the President replies. In the ensuing silence Jayasuriya, who also is the Leader of the Sri Lanka Working Journalists Association (SLWJA) reformulates the question.

“So if you finalize . . .” “People in glass houses should not throw stones”, the President interrupts, his eyes glowing with anger. After giving his answer he gazes obliquely up at the ceiling. Presidential anger fills the room, as I understand it primarily directed against the source of the question rather than the questioner himself.

Svenska

Svenska English

English